India Himalayas 2015

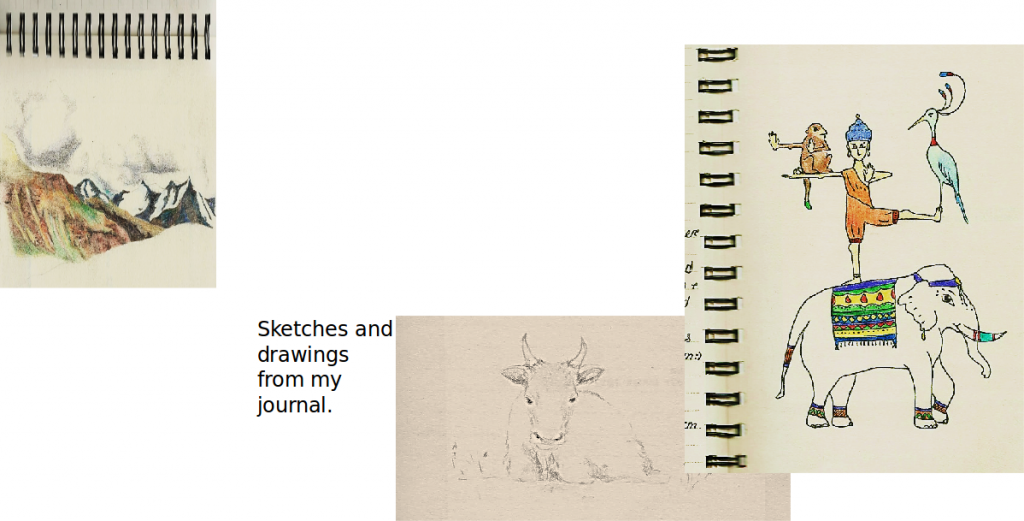

In this report I discuss my five week expedition to the Himalayas with the British Exploring Society (BES). The report is a summary of my experiences and personal development. I have also included photos and sketches from my journal.

Hannah Gillie

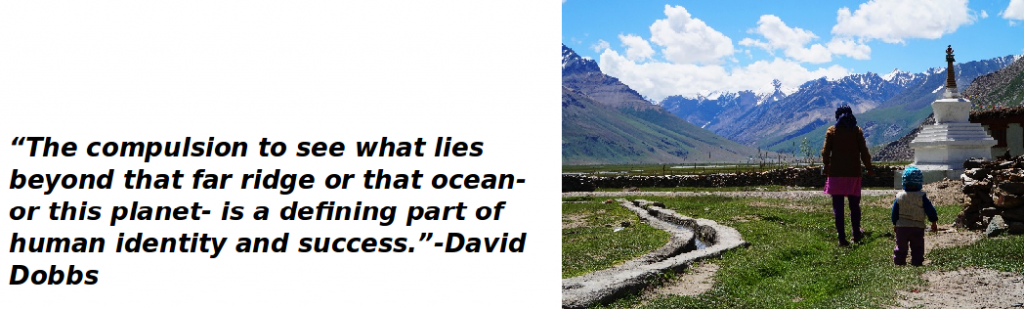

As I stared at this quote on the door of the Cambridge Cotswold changing room, weighed down with new hiking and camp gear, the reality of my forthcoming adventure truly began to sink in. After completing my first year of Geography at Cambridge University my keen interest in people, cultures, landscapes and the interactions between, combined with a passion for the great outdoors, to create an eagerness for discovery, challenge and exploration.

The British Exploring Himalayas 2015 expedition instantly appealed to me. The society’s history, first-class technical and scientific leaders and ethos of taking youngsters to the most inaccessible, challenging and inspirational wilderness areas of the world sparked my enthusiasm. Having been in Scouting for years and hiked a number of times in the Alps I was excited to follow in the footsteps of adventurous traders on ancient silk routes, learning new skills such as high altitude mountaineering and fieldwork whilst developing my communication and teamwork skills.

In January this year, having gained my place through a long application and interview process, I began training and preparing. During the months building up to our departure on the 21st July I researched the region I was heading to, improved my fitness and worked to raise the funds. The BES training weekend in April was a great opportunity to meet the team and understand just how demanding yet exciting this trip of a lifetime was going to be.

In January this year, having gained my place through a long application and interview process, I began training and preparing. During the months building up to our departure on the 21st July I researched the region I was heading to, improved my fitness and worked to raise the funds. The BES training weekend in April was a great opportunity to meet the team and understand just how demanding yet exciting this trip of a lifetime was going to be.

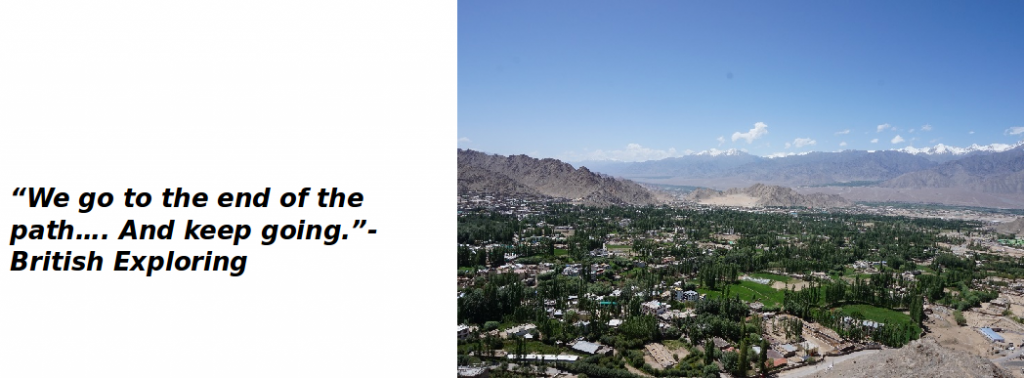

Our journey began in Delhi. From this humid chaos we travelled north into the disputed region of Ladakh and to its capital Leh. Ladakh (land of high passes) is a region in Jammu and Kashmir with average altitudes of over 3000m. Its culture and history are closely related to Tibet with Leh having grown as an important city on the ancient trade routes and Silk Road stretching from the Middle East to China. As we acclimatised in Leh and travelled by bus through the mountains on our way to base camp, I was fascinated by the mix of religions, of the ancient and modern and the harsh political as well as physical landscapes in which the Ladakhis were living.

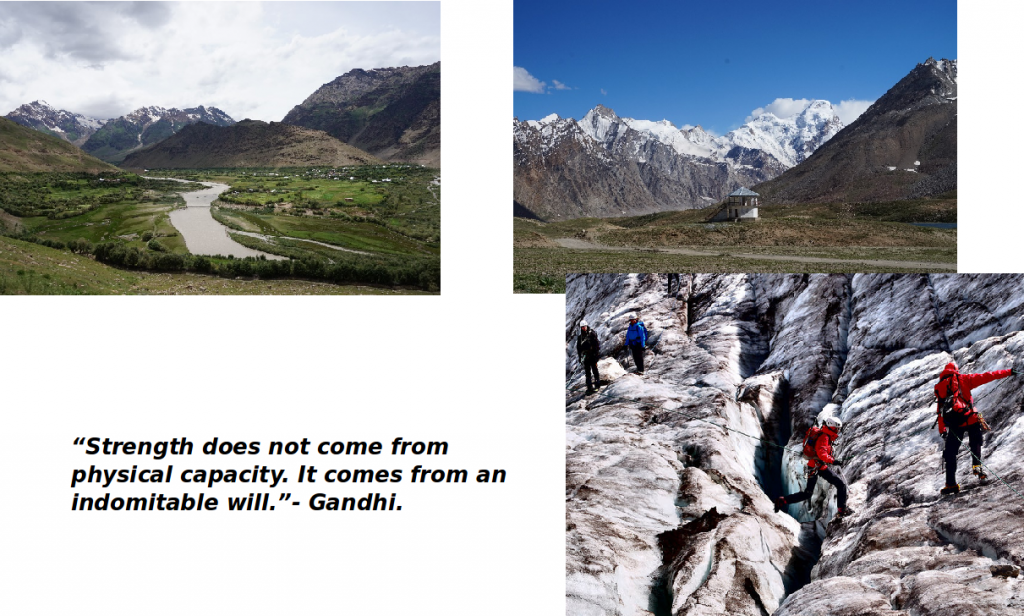

Ladakh is in the western region of the Tibetan Plateau which is known as a high altitude desert and as we left the lively green streets of Leh we were hit by the heat and dust of the open valleys and jagged crumbling peaks. The landscape formed by the closure of the Tethys Sea which was uplifted and compressed during the collision between the Indian and Eurasian tectonic plates about 50 million years ago, thus forming the folds and layers visible in the rock. The villages sat amid bright, lush green fields carpeting the floodplains in irrigated squares dotted with yaks and women harvesting. The beauty of survival in a harsh and unforgiving land.

Approaching Kargil on our second day travelling to base camp there was a transition from a predominantly Buddhist culture to a Muslim one. As a border town between Pakistan and India, Kargil had a tense and frequently violent existence making it geopolitically very interesting. Throughout the journey there was a huge Indian military presence. As our convoy of busses and supply jeeps progressed up the Suru valley towards the Zanskar my window seat became both a curse and a blessing. I enjoyed the wind and the sun but, when clinging to the seat as we bounced along dusty, hole strewn tracks overhanging cliffs, I was sick with nerves.

Base camp, home for four weeks, was the wilderness of Pensi-La, a mountain pass of 4400m between the upper Suru and Zanskar valleys. We were surrounded by snowy peaks tickling the sky at over 6000m, its bleak beauty reflected in several large turquoise lakes and enjoyed by the alpine flora which danced in bright colours in the thin mountain breeze. The land is baked by the sun, shaped by the wind and water and scarred by man.

At numerous times during our life in and around base camp I reminded myself of this quote; scrambling for hours up to a summit, jumping over crevasses on a glacier or even struggling to get the stoves working, it was steady determination which pulled you through.

There were about 80 people on the expedition and we were split into smaller teams called fires which included young explorers, a mountain and science leader and two trainee leaders. We spent the majority of our excursions and activities in our fires and by the end of the trip our team felt more like a family. Over the first few days at base camp we learnt a lot of mountaineering, camp and science skills along with first aid and how to keep healthy at altitude.

Mountaineering

It was tricky but fun learning how to scramble up rocks, to trust your sturdy B2 boots and how to rope in and rock climb. There were no paths and so understanding how to pick an ideal route was really important. A few hours was also spent river crossing training and we practiced daily with yellowbrick phones and GPS.

Ice training on the Drang-Drung glacier was one of the best experiences. With help from our mountain leaders and knowledge gained during my geography course I could read the glacier landscape, recognise its dangers and appreciate its dynamism and complexity. Using crampons and ice axes we learnt how to walk roped together as a team on the ice and how to make a crevasse rescue anchor. As I used my axe and crampons to climb up a vertical ice cliff, above a crevasse into oblivion, I had never felt more alive. In week four I returned to the glacier for a three day ice tour during which we hiked almost 20km up the ice. Between the ablation and accumulation zones the glacier completely changed in appearance from steep and rolling to flat ice crisscrossed with fractures and rivers. Two freezing nights were spent camping on the ice with avalanches and rock falls regular reminders of the extreme and unpredictable environment.

The greatest shock however, was when we came across an old wooden axe stuck in the ice. With much excitement we searched the area and managed to find a carved wooden stick, a soft woven boot, a pin and various pieces of bone including several teeth. It was an exciting discovery and interesting to speculate at who this had been and how they had died; perhaps a trader crossing the peaks caught in a storm, or a victim of the vicious ice, crushed and spat out after many decades within.

Coping with the cold of the glacier was a battle easier won than that of the daily struggle with altitude. It was frustrating fighting for breath after several steps up, as well as the frequent head rush and waking up every night breathless. We had to constantly monitor our own and each other’s health using the Lake Louise Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS) criteria. Little is currently known about why people react so differently to altitude as a number of people on the expedition suffered bad AMS whilst others were fine. Luckily, I had very few side effects and managed to avoid any serious illness.

After a week of acclimatisation a few of us from my fire attempted a 5400m peak in one day. It was super tough. My legs, lungs and feet were each in their own personal hell but the sense of achievement at the summit (and the fudge my leader had brought as a treat!) were well worth the pain.

When the final week at base camp came I opted for one last challenge; a five day fast and lightweight trek out of camp across a 5250m pass to meet the bus on its way back to Leh. It was a hugely demanding hike, both physically and emotionally. There was a nerve-racking river crossing and a long, arduous ascent up to the pass where we were rewarded with stunning views and snow leopard footprints in the ice. We had tempted fate with our lack of tents and sat through rain most evenings making sleeping in bivvy bags an uncomfortable experience. The silver lining was the sky, which each night was clear, bright and frosty.

These activities in the mountains taught me a great deal about leadership, the importance of team work and survival in harsh and remote terrains.

Camp and culture

Four weeks under canvas was the longest I had ever spent camping. Turning base camp into our home involved setting up toilet areas, a washing tower, mess tents and a cooking pit. Filtering water and cooking on small kerosene stoves was an everyday team effort, as was chasing away the curious yaks which sought our food. On rest days at base camp we did yoga, washed our clothes, swam in the lake and sketched. As a fire, we spent many happy evenings playing games and chatting. During the day a thin layer of sandy dust covered everything and at night the silver, dusty smudge of the milky-way arched across the sky. My most reflective and thoughtful moments were whilst I was gazing at that inky rip in the universe surrounded by millions of points of light.

Immersing myself in the culture and experiencing the lives of the locals was an important and enriching process. During the short four month Himalayan summer, yak herders live in small rock huts in remote valleys, grazing and milking their cattle. We were often given bowls of milk and yoghurt with ‘tsampa’ flour to eat. One night a team of us slept in an empty herder hut and cooked on yak dung fires, learning to live in the timeless patterns of the people. My mind was opened to the practice of Buddhism and how it is a seamless and ancient part of the landscape. Whilst staying the night in Rangdum ‘gompa’ (monastery) I talked to the monks who encouraged me to question my own lifestyle and religious choices. I enjoyed the peace and spirituality of the place.

The Ladakhis were so welcoming and hospitable. One of my favourite experiences was spent with a family who had offered to make us tea and lunch. I helped the mother to chop vegetables and make chapatis. She also showed me the tiny local school where she taught; there were only four children ranging from three to eight years old and they read to me in English. It was a beautiful and humbling few hours we shared in their world.

Science and health

Throughout the expedition there were a number of ongoing science projects: plant ecology, lake sediment coring, oxygen isotope analysis, diatoms, meteorology, glaciers and medicinal flora. These enabled us to discover and learn about new environments, develop fieldwork skills and explore our own ideas and questions through practical science. I was particularly involved in the flora, isotope and lake projects. I did detailed sketches of the flowers at base camp and identified, by use of photos and guides, a variety of species. By using books and talking to the local medicine men called ‘amchis’ we documented the medicinal use of the flowers and learnt about the ancient amchis’ practice. They diagnose by the colour of your tongue and, as depicted in the Buddhist wheel of life, your suffering is caused by the pig (stupidity and laziness), the bird (attachment and desire for example to material objects) or the snake (anger and hatred). When out of balance one becomes ill either physically or mentally. Although traditional, I believe such concepts are still relevant in our lives today.

I also collected water and ice samples for analysis back in the UK. The sample had to be airless and its location logged. They will be analysed using a mass spectrometer and the isotope ratios of oxygen and hydrogen determined. Oxygen for instance has two common isotopes oxygen-16 and oxygen-18, whose ratios vary naturally in samples such as water. This is called an isotopic signature. Oxygen ratios in the atmosphere and therefore in the water and ice vary with geographic location due to global weather patterns and regional topography for example. Thus the isotopic signatures sampled in and around base camp can be compared to known signatures from other parts of the region and wider subcontinent, in order to determine where the water originated. This data can be combined with knowledge of the Asian monsoon and Himalayan meteorology to construct past and present weather patterns in the sample locations.

Finally I helped create a depth profile of the largest base camp lake. We took a small inflatable boat out onto the lake and used a GPS and electronic water depth meter. This data will be used to create a 3D depth profile of the lake. Additionally, lake sediment cores were taken in order to reconstruct past climate, a study known as paleoclimatology. The width and chemical composition of the sediment layers reveal past climatic conditions such as deposition rates, thus weathering rates and the overall weather conditions at the time. Participating in such studies developed my sampling, mapping and research skills.

An important aspect of the expedition was using creative media to explore, capture and communicate. I was a member of the ‘Explorers’ Stories’ working group, a production team aiming to create a short film and education resource pack. We had several meetings throughout the trip in order to discuss the storyboard for the film. We decided on the title ‘What can we learn from Ladakh?’ I contributed to the filming by shooting my own footage, being interviewed and by presenting an introduction to Ladakh. I focussed also on capturing the expedition through writing, sketching and photography whilst reflecting philosophically on the whole expedition experience by completing pre-and post-expedition questionnaires.

The questions explored personality and motivation, coping with challenges and general well-being before and after the five weeks. When I compared them, there was a huge difference especially regarding feelings such as enthusiasm, energy and happiness, how I approach problems and opinions about aspects of my life like self value, religion and relationships.

When I asked our expedition chief leader Andrew Stokes-Rees about what drives him to spend weeks and months exploring the wilderness he said simply, that it was ‘a reconnection with humanity’. I considered this motive a great deal both at the time and since returning home. Only a small percentage of the planet’s population lives with the luxuries of a modern ‘western’ lifestyle; central heating, the internet, running water. Therefore such an expedition enables you to ground yourself, to reconnect with how the majority of the population lives. It is about living with nature not on it, reviving the ancient, more intimate relationship humans have with their environment. At home we seek things to keep us healthy and entertained like going to the gym or to the cinema for a thrill. But in the wilderness we experience those aspects of life, emotions in particular, in a more balanced way. The adrenaline from climbing a peak, the satisfaction of repairing ripped trousers and the camaraderie of your team.

Having never travelled outside Europe the trip has completely changed my perspective on life. Staying with Ladakhi families, the monks in the gompa and camping in the mountains has taught me new values and made me realise what is truly important in life. Community, self-respect and purpose are key to happiness and peace, as is compassion for others. Returning home was a greater culture shock than going and I feel that in our materialist lives where time is the most scarce commodity, we have somewhat lost the importance of those core values. Overcoming the physical and mental challenges of exploring and living in the Himalayas has certainly changed me. It has changed my priorities about what is important in life, influenced my faith and encouraged a stronger appreciation for simple amenities.

This adventure has enabled me to reflect on personal values and motivations and I have greatly expanded my geographical knowledge. With two years of study left I believe that my energy, interest and determination will enhance my passion for human and physical sciences but above all, will inspire and enthuse others.

One Response

I really enjoyed reading this account Hannah.