Richard was born on 17 November 1937 in the Lancaster Royal Infirmary to Ruth née Ainsworth (a children’s author) and Frank Gilbert (a chemist). He died on 16 January 2018, aged 80, in York Hospital after a short final illness.

He was educated, mostly, at St George’s School in Harpendon in Hertfordshire, one of the country’s first co-educational boarding schools, and at Worcester College (not co-educational in his time), Oxford, where he read Chemistry in his spare time between climbing week-ends and mountaineering vacations.

In between school and university he undertook his National Service, being commissioned into the Corps of Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers (REME) and on being demobbed in 1958 he celebrated by hitch-hiking to Skye with his brother Oliver to climb in the Black Cuillin, in later life gleefully remembering that their lift from Glen Garry to Sligachan was with Dame Flora MacLeod of MacLeod, the 28th chief of the Clan MacLeod, in a chauffeur driven Rolls Royce.

He married Trisha Roberts on 1 September 1962, raising a family of four children: Tim, Emily, Lucy and William; they lived in the village of Crayke in North Yorkshire, nestled in the Howardian Hills.

Richard enjoyed a career as a chemistry teacher at the Benedictine Ampleforth College in North Yorkshire for some three decades, despite himself being an atheist and a member of the York branch of the British Humanist Association; he could be relied always by his friends on being able to report on the latest episodic behaviour of the monkish community. By all accounts he was a popular and excellent teacher, with pupils in his classes frequently attaining examinations grades far above expectation. His other great claim to fame as a schoolmaster, of course, was his love of climbing and mountaineering in that he took charge of the Ampleforth College Mountaineering Club and was one of the first to embark on overseas expeditions. He taught the boys (for Ampleforth was single-sex boarding school during his time teaching there) to rock climb on local crags (one of the early participants being Joe Simpson of Touching the Void fame), and he led groups on frequent trips to Scotland, enjoying back-packing and camping adventures in the Cairngorms and up challenging peaks, often in winter conditions in March. These Scottish adventures prepared him and the boys for five overseas trips – to the Myrdals Jockull Ice Cap in South-east Iceland 1968, the High Atlas Mountains of Morocco 1970, the Trollaskagi Mountains of Northern Iceland 1972, The Lyngen Peninsula of Arctic Norway 1974 and, finally, Kolahoi in the Indian Himalaya 1977 (for which Richard was award a Winston Churchill Travelling Fellowship, presented to him by Her Majesty the Queen Mother at Buckingham Palace). These expeditions had been preserved for posterity in Young Explorers and the Kolohoi expedition, reputedly the first climbing expedition by a group of British schoolboys to the Himalaya and which concluded in a successful ascent of the 17,800ft / 5,456m peak, is recounted in an article by Richard in The Alpine Journal.

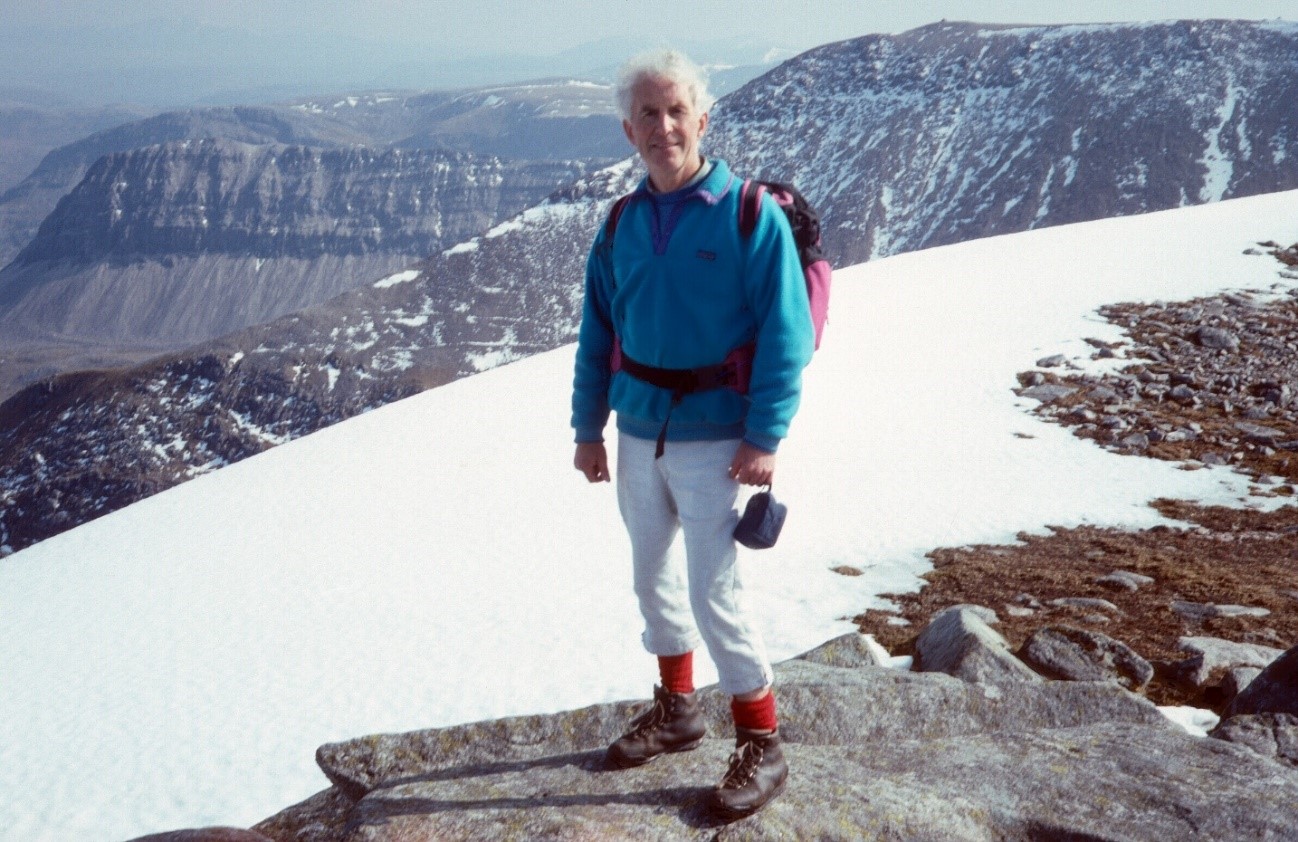

Richard’s own personal adventurous activities had commenced before his teenage years when at age 11 or 12 he had cycled 70 miles with his friend Myer Salaman to a youth hostel in Essex. As soon as he left school he and 2 friends attempted the Three Peaks Challenge [Ben Nevis, Scafell Pike and Snowden in 24 hrs.] with a Renault 4-chevaux support vehicle, but they ascended the Ben too quickly (2h 35min from Glen Nevis) and burnt out in the Lakes. Up at Oxford he joined the Mountaineering Club (OUMC – of which he was eventually President) and a popular local climbing venue was the brick facing of a railway tunnel near the village of Horspath – “The Horspath Horror” – which traversed across above the tracks, and the “Horror” became obvious when they had to try to hide their faces from the steam and smuts when a train passed close beneath them. Most term weekends spent rock climbing in North Wales or Derbyshire with vacations spent in the Lake District and Skye and winter climbing in Scotland. He remembers that his hardest climbs were probably Diagonal, on Central Buttress of Scafell and a full winter ascent of the North-east Buttress of Ben Nevis, and one of his most memorable was the whole Cuillin Ridge on Skye in a summer’s day. He had met his future wife Trisha on one of these club weekends in North Wales and he was delighted when she agreed to spend a day on Tryfan with him, where they apparently got benighted! He wrote to his mother about it: “I’ve met a really tremendous girl…”. Summer vacations were spent climbing in the Alps with OUMC friends such as Nigel Rogers, Colin Taylor, Alan Wedgewood, and his brother Christopher. On one occasion, along a ridge on the Allalinhorn with Alan and Janet Wedgewood, Richard was roped to a less experienced person who slipped and fell. He was quick thinking and leapt six foot off the other side of the ridge to arrest the fall. Other memorable Alpine days while a student included the ascents of the Matterhorn and the Dent d’Herens. He pretty much gave up pushing himself out of his comfort zone on hard technical rock climbs after a fall off Agrippa on Craig yr Ysfa in the 1960s when he was leading and had casually looped a sling over a protruding bit of rock early on but had not put in much more protection further up the climb. As he grabbed up for a hold that piece of rock came free and he took a massive fall but was held by the early sling, and hung upside-down, his head just an inch from the ground. This, together with recently having lost several friends (such as Colin Taylor who died on the Obergabelhorn in 1974) and having started his family with Trisha, took away his enthusiasm for hard rock climbs. Hpwever, his love of the Scottish hills, especially in winter or spring conditions, helped divert his interests away from rock climbing and onto hill walking, concentrating on the Scottish Munros and non-technical Alpine ascents, as well as mountaineering (but not climbing) in Norway, Iceland, Atlas, the Rockies, and the like. In 1971 he completed all the Munros by ascending Bidean nam Bian in Glen Coe on 12 June, becoming the 101st Munroist. [See his book Memorable Munros]

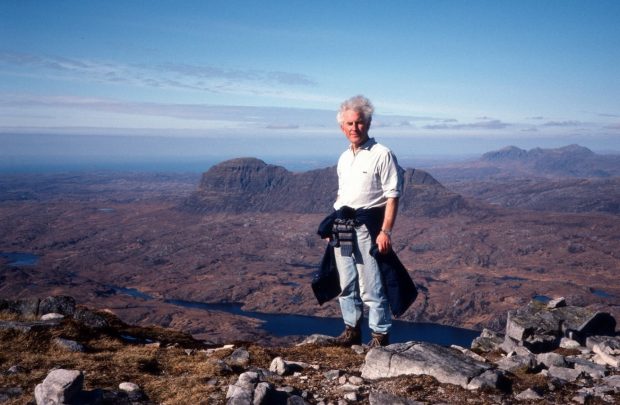

On Cul More looking to Suilven, NW Scotland

Richard and Trisha had frequent family holidays in the Austrian Tyrol, hut-to-hutting and climbing peaks, with three of their children (Tim, Lucy, and William). This began as soon as the children were deemed old enough in 1982 when Tim was 16 and Lucy was 11 years old; too small to wear crampons, they ascended, amongst others, the Zuckerhütl, the highest peak in the Stubai Alps (3,505m / 11,499ft). For this purpose Lucy was given her first ice axe the preceding Christmas (when she was 10), and her father tested that she was ready for the Alps by taking her up An Teallach at Easter in full winter conditions in a gale. Most other family holidays were hill walking and camping on islands and remote areas of north-west Scotland where Richard bought a plot of land on the Braes above Ullapool and had a small house built in 1970, looking over Loch Broom, Ullapool, Ben Gobhlach and through to An Teallach and east to the Beinn Dearg range. Often with Trisha he undertook several long-distance walks, such as the Welsh Three-Thousanders, The Lakeland Three-Thousanders, the Lyke Wake Walk, Marsden to Edale, the Yorkshire Three Peaks, the Karrimor and Saunders Mountain Marathons and the Great Outdoor Challenge (coast-to-coast backpacking hike). Other expeditions with Trisha included: the Wind Rivers Range in Wyoming where they climbed the highest peak of the range, Gannet Peak, and trekked to the cirque of Towers; the Alaska / Yukon old rush Chilkoot Trail; and the traverse of the Karakoram Range up the Biafo Glacier to Snow Lake and down the Hispar Glacier to Hunza. In 1990 they joined a Karakorum Experience expedition to Svanetia, Georgia in the Caucasus to climb Mount Elbruz (5642m), the highest peak in Europe. Due to the cold war, this was the first formal expedition from the UK to visit the range since John Hunt’s expedition in 1958. See article in the Alpine Journal.

Despite being a scientist, Richard was a prolific writer, coming as he did from a family of writers (grandfather Percy Ainsworth wrote poems, sonnets and famous Methodist sermons; mother Ruth Ainsworth was a well-known children’s author and poet; brothers Christopher and Oliver wrote books on Chippendale and botany / lichens / ecology respectively). As well as occasional articles published in The Alpine Journal, Richard was a regular columnist for High Magazine – “Richard Gilbert’s Walking World”. He wrote several mountaineering / hill walking books, including the best-selling coffee-table series with Ken Wilson: Big Walks, Classic Walks, Wild Walks. A 1980s Channel 4 TV series was based on these called “Great Walks”, two of which featured Richard (Malham, with his brother Oliver, and Cape Wrath to Sandwood Bay with his wife Trisha and younger children, Lucy and William). His best-selling book Exploring the Far North-West of Scotland won “Highly Commended” in the guidebook category of the Outdoor Writers and Photographers Guild in 1995.

His bibliography:

- Memorable Munros (1976, 1978, then by Diadem Books Ltd 1983)

- Hillwalking in Scotland (1979, Thornhill Press)

- Young Explorers (1979, GH Smith & Son)

- The Big Walks (1980, Diadem Books Ltd)

- Mountaineering for All (1981, Batsford)

- Classic Walks (1982, Diadem Books Ltd)

- Wild Walks (1988, Diadem Books Ltd)

- Richard Gilbert’s 200 Challenging Walks in Britain and Ireland (1990, Diadem Books Ltd)

- Exploring the Far North West of Scotland (1994, Cordee)

- Lonely Hills and Wilderness Trails (2000, David & Charles)

- York – a photographic history of your city (2002, Black Horse Books, WH Smith)

Perhaps because he was a scientist, Richard was an active campaigner for outdoor access, the environment and (in particular) Scotland’s wild land and was a long-term member and supporter of the John Muir Trust and Scottish Wild Land Group. As well as the mountains, he had a love of wild places in general, especially the Scottish Islands. Although he suffered terribly from sea sickness, he twice chartered boats to take him, his family and his friends to St Kilda in the 1980s. He arranged for a fisherman to take the family to Priest Island (the remotest of the Summer Isles) for a camping trip, but they had to be taken off early to beat a Force Eight gale. Other family holidays included the Outer Hebrides and later in life Trisha encouraged him to discover Shetland. What he termed “vandalism” of wild places, such as hydro-electric schemes marching across wilderness, angered him immensely and he was at the forefront of many a campaign to preserve wild spaces. He had a deep love of music, Mozart and Haydn to the fore, and was a Friend of the Ryedale Festival. He simply could not stand cruelty to animals, especially hunting with dogs. He was a great cricket and rugby fan, playing cricket at school and university.

Group in training in Scotland for a Himalayan Expedition

As known to many but not all his friends, Richard was plagued with a hereditary kidney disease: polycystic kidneys, where kidney function gets progressively worse with time owing to increasing cysts. He had to start dialysis in 1998 when he was tied to a machine for four hours per session, three times per week. Despite this, he managed to maintain his adventurous lifestyle by arranging visiting dialysis sessions in Inverness, Mallorca, New Zealand, and wherever. He was on dialysis for nine years before receiving a kidney transplant. Before that, however, he needed open heart surgery for a mitral valve replacement to make him fit enough for the transplant operation. The new kidney was a great success and he was free again to travel to the Lake District and the Scottish Highlands and Islands. However, long-term dialysis and transplants (with anti-rejection drugs suppressing the immune system) came at a major cost to his health, and he suffered frequent infections, other illnesses and weakness. Probably because of the massive toll on his heart through dialysis, he had a major stroke in 2014 that partially paralysed his left arm and left leg so that afterwards he could only walk short distances with a stick (or long distances in a wheelchair). He fought hard to recover from the stroke, relentlessly doing his physio exercises to get back as much movement as possible, and he maintained his positive attitude and outward spirit by acquiring an automatic car with steering wheel gadgetry that enabled him to drive to the Lakes, the Dales and even, in 2017, to Ullapool.

In all a life of eight decades (during which he defeated his illness on so many occasions), packed full of a huge variety of activities, built around his professional career (where his schoolmastering went so much beyond the classroom), his family (in whose many successes he rejoiced) and the hills (where he went to repair his spirit). He leaves his wife and children, of course, but very many friends and colleagues around the outdoor world to mourn his passing.